The Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution banned the production, importation, transportation and sale of alcoholic beverages, and this time became informally known as the Prohibition era. The separate Volstead Act or National Prohibition Act, set down methods for enforcing the Eighteenth Amendment, and defined which "intoxicating liquors" were prohibited, and which were excluded from prohibition. Following ratification in 1919, the effects of the amendment were long lasting, with some cities experiencing increases in crime due to the many forms of illegal alcohol production and distribution through speakeasies and bootlegging, as well as illegal distilling.

Law enforcement soon found themselves overcome by the rise in illegal, wide-scale alcohol distribution and associated crimes. The enormity of their task was unanticipated and relevant law enforcement agencies realized quickly that they lacked the necessary resources to fight the surge in crime. Increasing numbers of bootleggers would use women to help smuggle their alcohol as several states had laws preventing male agents from frisking or otherwise searching female suspects, creating the urgent need for female law enforcement officers.

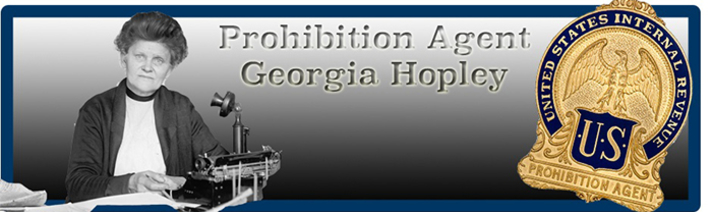

In 1922, Georgia Hopley became the first female Internal Revenue Service agent when she was sworn into office as the first prohibition agent, in the Prohibition Unit in Washington, D.C. President Warren G. Harding appointed Georgia to be the director of constructive publicity for the bureau. She had previously been named a special agent of the State Bureau of Labor Statistics to examine working conditions for women after representing the women of Ohio at the Paris Exposition in 1900.

During her two years with the agency, Georgia spent her time leading the development and implementation of the bureau’s efforts to reach out to the public. She traveled across the country speaking at events and wrote articles discussing the prohibition enforcement issues including the increase of female bootleggers.

In one of her interviews with the Boston Sunday Globe in March 1922, she talked about women being better suited to catch women. “[Women] resort to all sorts of tricks, concealing metal containers in their clothing…their detection and arrest is far more difficult than that of male lawbreakers.”

Georgia didn’t see her job as detecting lawbreakers. As she told women during a dinner at the Grace Dodge Hotel, “[My task] is to arouse in all classes, a spirit of willingness to observe and obey the law.”

Much of her philosophy was centered on a quote she valued by President Abraham Lincoln which said, “Let reverence for the laws be the political religion of the nation.”

During this time, she worked on establishing a national law enforcement day after successfully campaigning for it in her home state of Ohio. Georgia believed women needed to “awaken to their responsibility in law enforcement” and law making.

After leaving the bureau in 1924, Hopely continued her career in journalism, focusing on women’s suffrage which increased her stature as a political figure.

Georgia Hopley passed away after a long battle with an illness on July 1, 1944.

Sources

- Toledo Blade: Saturday, July 1, 1944. Death Ends Career of Georgia Hopley

- Photo: (1922) Miss Georgia Hopley. 1922. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress

- Evening Star. First Woman Prohibition Agent Says Her Sex Must See to Law Enforcement. March 12, 1992

- The Charlotte News, Feb. 24, 1922 Miss Hopley is Great Worker

- Evening Star. March 17, 1922, pg. 5. When 100 Women Dine

- Whiskey Women: The Untold Story of how Women Saved Bourbon, Scotch

- Alcohol Problems and Solutions: Women Prohibition Agents Made Diverse Contributions

Other Resources

- Alexander C. T. Geppert: Fleeting Cities. Imperial Expositions in Fin-de-Siècle Europe, Basingstoke/New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

- Richard D. Mandell, Paris 1900: The great world's fair (1967)